Super Yacht Builders’ Guide to Counter-Cyclical Growth

By George Morton, PhD, January 2026

Executive Summary

Dow Theorist Hamilton, in his 1922 book The Stock Market Barometer: A Study of Its Forecast Value, described the averages as a reliable barometer for forecasting trends in business activity (including industrial aspects). He emphasized its predictive power for economic/industrial conditions beyond just stock prices.

This paper proves Hamilton’s insight right when we apply the Dow Theory to the Super Yacht Builders Industry.

Super Yacht Builders operate in an industry where construction decisions made today have a significant impact on profitability over the next two to three years. This 24-36 month construction timeline creates both substantial risks and extraordinary opportunities. The critical insight is recognizing that risk mitigation does not require accurate market forecasting; it requires discipline to act counter to current market sentiment, guided by objective signals from equity market analysis.

The luxury superyacht industry exhibits a notable and significant correlation with equity market cycles: superyacht orders display a weak negative correlation with the same-year S&P 500 performance (-0.113) but a strong correlation with the growth of the ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) population (0.544). This relationship reveals a fundamental truth: builders who follow current stock market sentiment systematically commit capital at precisely the wrong moments. Builders who follow objective market timing signals, such as those provided by Jack Schannep’s modernized Dow Theory, position themselves to expand during periods of maximum industry pessimism and contract during periods of maximum euphoria.

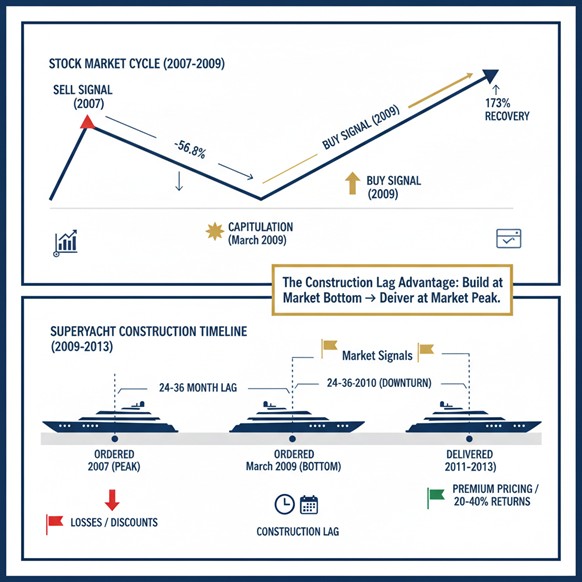

The historical record from 2007 to 2025 provides decisive evidence. Builders who committed to construction in March 2009 (at the market bottom) delivered vessels in 2011-2013 into a recovering market, capturing return premiums of 20-40% compared to average-market constructions. Conversely, builders who committed during the 2006-2007 peak delivered in 2009-2010, only to face a collapse, with massive discounts and write-downs. The pattern repeated less severely in 2021-2022, with builders who over-committed during peak euphoria facing softening demand and pricing pressure in 2023-2025.

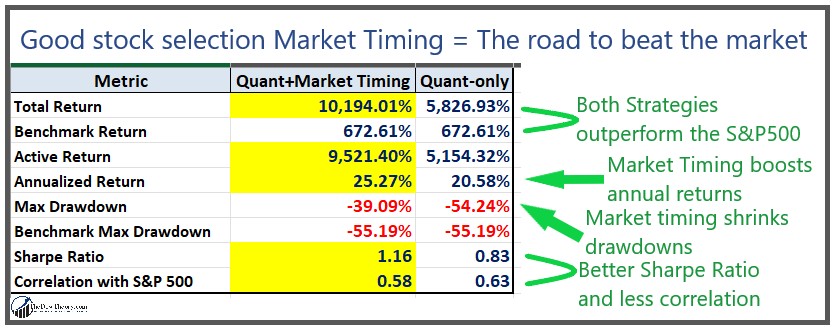

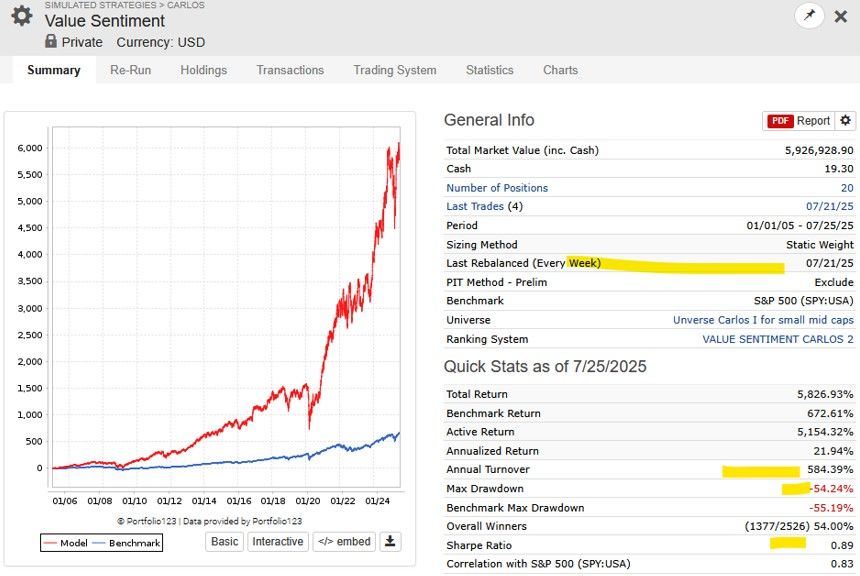

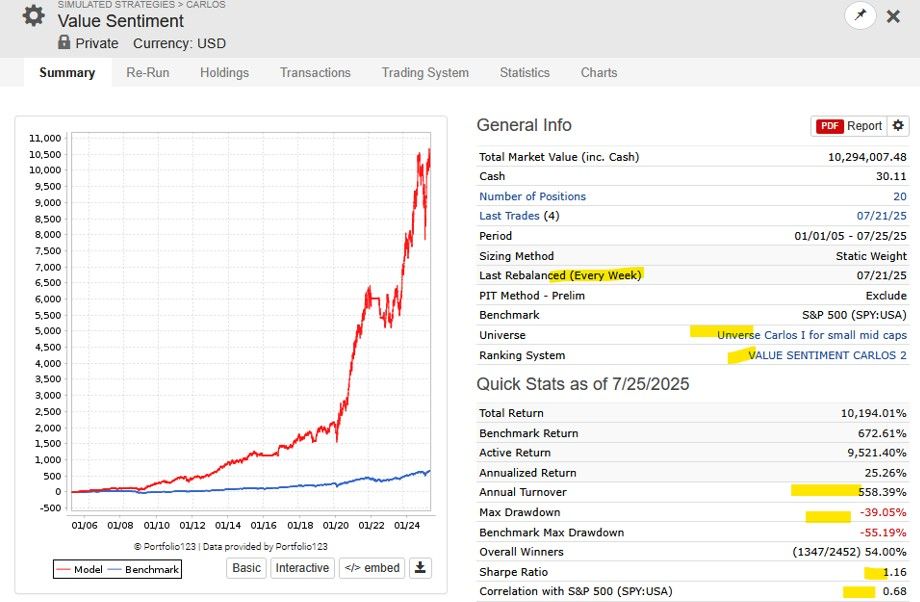

By integrating Jack Schannep’s New Dow Theory signals (DT21C)—SELL, CAPITULATION, BUY—into capital allocation decisions, Super Yacht Builders can systematically reduce risk while expanding at optimal moments. This paper demonstrates how objective market timing significantly enhances construction timing decisions, and why the next 12-24 months offer specific strategic guidance based on current Dow Theory signals.

Part One: The Fundamental Challenge — The Construction Lag and Market Cycles

Super Yacht Builders core challenge is not unlike that facing all superyacht builders: construction requires 24-36 months, yet market conditions shift far more rapidly. A superyacht ordered in January delivers in January 2027 or 2028, but market conditions in those delivery years cannot be perfectly anticipated when commitment decisions are made. This temporal gap is typically viewed as an unavoidable risk, the uncertainty inherent in any long-cycle manufacturing business.

Yet this temporal gap is not merely a risk; it can become a strategic advantage when construction timing aligns with market cycles. To understand why, we must examine what happens when construction timelines synchronize with wealth cycles.

When the S&P 500 reached its October 2007 peak of 1,576, the UHNW population globally stood at approximately 187,400 individuals. Superyacht orders reached an all-time high of 269 units, driven by euphoric market sentiment and the wealth effect flowing from years of strong portfolio performance. Builders, responding to this surge in orders, committed to aggressive speculative construction, expecting demand to remain robust.

What followed was instructive. The S&P 500 declined 56.8% from peak to the March 2009 bottom of 676.53. The UHNW population contracted to 166,000 individuals—an 11.4% decline in the core customer base. Superyacht orders collapsed to 112 units, a devastating 58% decline.

Yet here is the critical insight: despite the order collapse, superyacht deliveries continued from vessels already in the construction pipeline. Those boats, ordered during the 2005-2007 peak, were delivered in 2008-2010 into a severely depressed market. Buyers faced the choice of accepting massive discounts, canceling orders entirely, or, in many cases, allowing yards to seize superyachts and liquidate them for pennies on the dollar. Between 2009 and 2014, more than $5 billion in enterprise value was lost from the superyacht manufacturing sector due to pro-cyclical construction decisions made during peak sentiment.

The inverse scenario proved equally decisive. A few disciplined builders who committed to construction in March and April 2009, when industry sentiment was at its most pessimistic and competitors were cutting capacity, positioned themselves for delivery in 2011-2013. During those years of delivery, the S&P 500 recovered 173% from its March 2009 low. The UHNW population rebounded to 199,200 by 2013, and superyacht orders recovered to 180 units annually. These counter-cyclical builders, constructed during periods of maximum fear at minimal construction costs, were delivered into a recovered market at premium pricing. Their return on construction cost enhancement typically reached 20-40% compared to vessels built at average market conditions.

This 2008-2013 cycle was not unique. The 2020 COVID crash provided a parallel lesson. The S&P 500 declined 33.9% from February to March 2020, then recovered dramatically due to the unprecedented intervention of the Federal Reserve. Builders who committed to construction during the March panic, when uncertainty was at its maximum, found themselves delivering into 2022-2023 when superyacht orders had reached record levels. The UHNW population benefited disproportionately from Fed asset purchases, and demand for private assets surged. These counter-cyclical builders captured the most substantial surge in demand for superyachts in history.

The pattern is clear: successful superyacht construction timing is not about forecasting. It is about understanding market cycles and having the capital discipline to invest counter-cyclically.

Part Two: Understanding the Wealth Effect Lag — Why UHNW Individuals Buy Superyachts with a Delay

The empirical data reveal a curious disconnect between superyacht orders and the same-year S&P 500 returns, which show a weak negative correlation (-0.113), but a moderate positive correlation with prior-year S&P 500 returns (0.299). This lag effect is not random; it reflects how UHNW individuals process changes in wealth and make discretionary spending decisions.

When equity markets suffer severe declines, UHNW individuals initially respond by reassessing portfolio positions and shifting to defensive postures. They do not immediately commit to multi-million-dollar discretionary assets. Instead, a psychological transition unfolds over approximately 12-18 months. During the first phase (months 0-6 after market bottoms), wealth appears temporarily depressed, and psychological confidence remains compromised. Superyacht orders collapse. The March 2009 bottom generated only 112 orders, despite marking the beginning of the recovery. The March 2020 COVID bottom produced 250 orders despite the historic market crash.

However, by 12-18 months after market bottoms, the psychological transition is complete. Existing UHNW individuals see their portfolios substantially recovered. New wealth creation resumes as market conditions improve. The wealth effect, the psychological confidence that translates portfolio gains into consumption spending, becomes fully operational. At this 18-month mark, UHNW individuals who delayed major luxury purchases now commit. This explains why superyacht orders reached 155 units in 2011 (18 months after the March 2009 bottom) despite the stock market showing only 0% returns that year. It explains why superyacht orders reached 300 units in 2021 (18 months after the March 2020 bottom), representing the highest superyacht volume in history.

This “second year” phenomenon, as Dow Theory expert Jack Schannep describes it, is the mechanism that transforms the construction lag from liability into advantage. Builders who commit to construction during market bottoms (months 0-6) will complete their vessels approximately 24-30 months later (months 24-30), which corresponds precisely to the peak wealth effect period. They deliver to the maximum demand and optimal pricing.

Critically, the strongest correlation in the data links superyacht orders not to market returns, but to UHNW population growth (r = 0.544). The global UHNW population has expanded from 166,000 in 2009 to approximately 510,810 in 2025, a 208% increase. This expansion creates a secular tailwind independent of market cycles. Even during the 2022 bear stock market, superyacht orders, at 310-280 units, far exceeded the 112-140 unit range of 2009-2010, despite the 2022 downturn being far milder than the 2008-2009 downturn. The larger UHNW base provides resilience and growth.

For Super Yacht Builders, this wealth effect lag and UHNW population growth combination creates a powerful strategic positioning. Builders can now rely on predictable behavioral patterns rather than uncertain forecasts.

Part Three: Jack Schannep’s New Dow Theory (DT21C) — Objective Signals for Subjective Decisions

The challenge facing Super Yacht Builders’ strategic planning is how to transform understanding of market cycles and wealth effects into disciplined capital decisions. Subjective market forecasting introduces bias and emotion. Financial analysts have a notoriously poor track record for predicting market movements. Yet superyacht construction decisions cannot proceed without some framework for timing.

Jack Schannep’s modernization of Charles Dow’s century-old theory, the Dow Theory for the 21st Century (DT21C), provides precisely such a framework. Rather than forecasting, Dow Theory relies on objective price signals—specific market conditions that have identified significant trend changes with documented accuracy over 120+ years.

Dow’s original theory, developed in the early 1900s, identified primary trends (lasting years) interrupted by secondary reactions (lasting weeks to months). Schannep refined this approach by adding specific enhancements: incorporation of the S&P 500 for broader market confirmation beyond the Dow indices, identification of capitulation events as entry signals marking bear market bottoms, and shortened timeframes for secondary reaction completion (from “weeks to months” to “ten to sixty days”). Most importantly, Schannep maintained a detailed database spanning over 60 years of historical signals, enabling performance analysis.

The three core Schannep signals correspond to distinct market phases and require specific responses from builders. A SELL signal occurs when primary indices confirm that bull markets have reversed into bear markets. Historically, SELL signals emerged in November 2007, months before the Lehman collapse materialized. The signal preceded the crisis because it derives from technical market confirmations rather than news events. When SELL signals appear, builders should immediately suspend new speculative construction commitments, complete existing contracted builds, and begin accumulating capital reserves.

CAPITULATION signals identify stock market bottoms with remarkable precision. Schannep’s database shows capitulation events occur on average in just 14 days and 4.6% above the exact ultimate market low. March 2009 marked the precise bottom at 676.53 with capitulation within days. March 2020 marked another capitulation. When capitulation signals emerge, they typically occur 4-6 months before full BUY signals are generated. This gap represents the optimal entry point for counter-cyclical superyacht builders. Super Yacht Builders should begin preliminary design and supply chain negotiations, secure favorable supplier arrangements, and commit initial capacity increases (approximately 25% of the desired expansion) if capital reserves permit.

BUY signals represent confirmed trend reversals with full index confirmation. Historically, BUY signals emerged in April 2009, approximately one month after the March 2009 capitulation. When BUY signals appear, all three major indices (Dow Industrials, Dow Transports, S&P 500) have confirmed durable uptrends. This is when Super Yacht Builders should commit fully to construction programs, aggressively pursue orders from high-quality clients, and secure long-term supplier contracts on favorable terms.

The performance record demonstrates the utility of Dow Theory with precision. A 173% advance followed the April 2009 BUY signal in the S&P 500 by December 2013. Superyacht builders who committed boldly during March-April 2009, when industry pessimism was profound, built vessels at minimum cost, secured supplier capacity before demand increased, and delivered into a recovered market. Similarly, the March 2020 capitulation, followed by the April 2020 BUY signal, positioned builders for the subsequent record-setting demand surge of 2021-2022.

The key insight is that Schannep signals remove emotion from construction timing decisions. Instead of asking “Do I feel confident the market will recover?” builders ask “What do the objective price signals indicate?” This objective framework proves dramatically superior to sentiment-based decision-making.

Part Four: Superyacht History as Strategic Instruction

The 2007-2025 period offers a rich historical laboratory for understanding the effects of construction timing. The superyacht market, defined as vessels 24 meters (79 feet) and larger, has evolved from a niche luxury market to a substantial industry reflecting global UHNW wealth dynamics.

In 2007, at the peak of the credit bubble, the superyacht market appeared to be experiencing unbounded growth. Orders reached 269 units globally. Fleet size exceeded 5,400 vessels. Builders worldwide expanded production capacity aggressively, expecting continued boom conditions. Financing was readily available, UHNW wealth was at record levels, and industry consensus predicted years of sustained expansion.

The reality proved catastrophically different. The Lehman collapse of September 2008 initiated a wealth destruction that reached 56.8% by March 2009. Superyacht builders faced a dilemma: massive production capacity with collapsing demand. Weak builders ceased operations. Established builders faced bankruptcy threats. Many yards attempted to maintain production in hopes of eventual recovery, burning cash and intensifying losses. Experienced builders contracted sharply but preserved core teams and supplier relationships, maintaining capital for eventual opportunities.

By 2010-2011, the divergence between builders became apparent. Those who maintained construction commitments in 2009, despite industry pessimism, now had delivery schedules in a recovering market. UHNW wealth was restoring. Superyacht demand was accelerating. These builders, particularly those with capital discipline and supplier relationships, commanded premium pricing and enjoyed exceptional margins.

The contrast to builders who had over-committed in 2006-2007 was stark. Vessels ordered during peak euphoria were delivered in 2009-2010 into depression. Buyers canceled or renegotiated prices downward. Yards faced massive write-offs. The superyacht industry documented cumulative enterprise value destruction of over $5 billion from 2009-2014, the vast majority attributable to builders who had committed during boom conditions and delivered during bust conditions.

This historical lesson has become deeply embedded in industry consciousness. By 2020, when the COVID-19 crash hit markets, confident builders with strong capital positions moved quickly into expansion mode during a period of maximum uncertainty. They reasoned—correctly—that the construction lag would result in delivery during the recovery period. The Federal Reserve’s unprecedented intervention ensured the protection of UHNW wealth, and demand indeed surged. These counter-cyclical builders who committed in March-April 2020 captured the strongest superyacht market in history, delivering record volumes in 2022-2023 with premium pricing.

However, not all builders learned these lessons. Euphoria drove some to overcommit in 2021-2022 as superyacht orders reached an all-time high of 350 units. Construction costs elevated as capacity constraints appeared. Delivery schedules extended. Then market conditions moderated in late 2022. Demand softened in 2023-2024. Builders who had committed at peak enthusiasm faced challenging delivery environments. Order cancellations and pricing pressure ensued.

The historical pattern is unambiguous: builders who coordinate construction timing with market cycles, through counter-cyclical expansion during capitulation and disciplined contraction during peaks, consistently outperform competitors who follow market sentiment.

Part Five: The Negative Correlation and the Value Destruction of Pro-Cyclical Construction

The empirical finding that superyacht orders exhibit a negative correlation with the same-year S&P 500 returns carries a critical warning: following market sentiment can destroy value. When markets rise and sentiment turns bullish, superyacht orders surge. Builders, observing the current strength of demand, commit to aggressive expansion. Yet this enthusiasm occurs precisely when markets are most vulnerable to reversal. Vessels committed during euphoria are delivered into weaker demand environments 24-30 months later.

This dynamic played out acutely during 2021-2022. Robust market performance (+26.89% in 2021, strong early 2022), combined with record UHNW wealth, drove superyacht orders to 350 units, the highest ever recorded. Builders, responding to current demand strength, are committed to maximum production. Construction costs have already risen due to capacity constraints. Competition for resources is intensified. Delivery schedules extended into 2024-2025.

Then in October 2022, markets corrected 19.95%. Superyacht orders are expected to moderate to 280-310 units in 2023-2024. Builders who had committed at peak enthusiasm faced several challenges: construction costs that were now 15-25% higher than those who had committed during 2020 trough periods; extended delivery schedules that placed completions into periods of reduced demand; compressed margins as delivery pricing faced challenges; and potential order cancellations from buyers who had committed during euphoria but now faced different circumstances.

The contrast to builders who committed in March 2020, despite maximum uncertainty, is instructive. Those superyachts cost 15-25% less to build. Delivery occurred in 2022-2023 during peak demand. Margins expanded. Returns on construction exceeded 20-40% compared to pro-cyclical alternatives.

For Super Yacht Builders, the negative correlation insight translates to a specific discipline: when Schannep Dow Theory signals ‘SELL’, immediately reduce speculative construction commitments, regardless of current order flow or industry pressure. The negative correlation proves empirically that bullish sentiment driving current orders will be followed by market weakness. Pro-cyclical expansion is a value-destroying trap that disciplined builders must resist through capital policies implemented before emotional pressure becomes overwhelming.

Part Six: Strategic Framework— Implementation Approach

Super Yacht Builders can operationalize Schannep Dow Theory signals into a practical framework for construction decisions. The first step is monitoring Schannep’s published signals, which are updated regularly and publicly available through The Dow Theory website. Rather than attempting internal market timing analysis, Super Yacht Builders’ strategic planners should reference these objective signals for major decision points.

When SELL signals appear, one should immediately implement a “contraction posture.” Suspend all speculative construction commitments. Complete existing contracted builds with full quality commitment. Focus on cash accumulation and maintaining a strong balance sheet. Maintain core technical teams and key supplier relationships through modified engagement, while avoiding expansion of capacity. This discipline, although psychologically painful when competitors remain aggressive and industry sentiment supports continued expansion, proves essential for capital availability during subsequent capitulation phases.

When CAPITULATION signals emerge, typically occurring 4-6 months after SELL signals, Super Yacht Builders should shift to “cautious entry.” Begin preliminary design and engineering work for select projects. Negotiate long-term supplier agreements at depressed pricing—Scout for potential client opportunities. Commit initial capacity expansion (approximately 25% of the desired total increase) if capital reserves are adequate. This measured approach allows Super Yacht Builders to establish favorable supplier terms and relationships without overcommitting before the formal BUY signal.

When BUY signals are generated, typically emerging a few months after capitulation, Super Yacht Builders should implement “aggressive expansion.” Move to full commitment on construction programs. Aggressively pursue orders from high-quality clients. Lock in suppliers at the favorable terms negotiated during capitulation. Expand capacity toward desired levels. This is when counter-cyclical construction delivers maximum advantage: Builders build at minimum cost, secure supplier capacity before demand surges, and position for delivery into recovered markets.

During the 8-to 18-month period following BUY signals, the “second year” period when the UHNW wealth effect becomes fully operational, builders should maintain maximum production. Superyachts begun during capitulation are now in final construction phases. Delivery pricing achieves premium levels as UHNW demand accelerates and backlog builds. This is when counter-cyclical construction delivers its maximum return: vessels built cheaply, delivered into peak demand, capture margin expansion. The current market stance is based on the Dow Theory, which suggests buying this summer, starting with the tariff bear market, implying that the market for superyacht orders will expand into 2026.

When subsequent SELL signals appear (typically 2-5 years after BUY signals), Super Yacht Builders returns to contraction posture. The cycle begins again.

This framework removes subjective forecasting and replaces it with an objective signal following. While no timing system is perfect, Schannep Signals’ documented accuracy over 120+ years provides far greater reliability than sentiment-based approaches.

Part Seven: Capital Management and Risk Mitigation

Even with disciplined signal following, superyacht construction involves substantial capital requirements and risks that require prudent management. Counter-cyclical construction necessitates sufficient capital reserves to fund speculative builds during periods of pessimism, when external financing is costly and constrained. Super Yacht Builders’ family-controlled ownership structure, compared to some publicly traded competitors subject to quarterly earnings pressure, provides advantages in maintaining a long-term perspective and preserving capital during temporary downturns.

Supplier and subcontractor relationships prove critical. Depressed construction environments during market bottoms create opportunities to secure preferential terms and long-term contracts, but only within relationships built on trust. Fair treatment of suppliers during normal times builds the foundation for partnership approaches during crisis periods. This relationship approach offers competitive advantages over builders who pursue purely transactional approaches.

Talent management requires a careful balance. Market downturns create pressure to reduce management and technical staffing drastically to preserve cash. However, premature talent reduction compromises the ability to execute counter-cyclical expansion when opportunities emerge. Retaining core technical teams through modified engagement models or reduced hours represents an investment in recovery-phase capacity and quality.

Client financial screening becomes critical during recovery phases when backlog builds and demand accelerates. The temptation to accept marginal clients increases precisely when discipline is most needed. Thorough verification of genuine UHNW status and financial strength prevents the order cancellations that plagued the industry in 2009-2010 as over-leveraged buyers exited when markets weakened.

Geographic diversification provides additional resilience. Super Yacht Builders’ dual manufacturing base in Taiwan and the United States creates flexibility for capacity deployment based on regional recovery timing. Regional UHNW wealth varies geographically, and market cycles impact different regions at different times. This flexibility enables more nuanced counter-cyclical strategies than competitors with single-region concentration.

Part Eight: Current Strategic Position and Forward Outlook (November 2025)

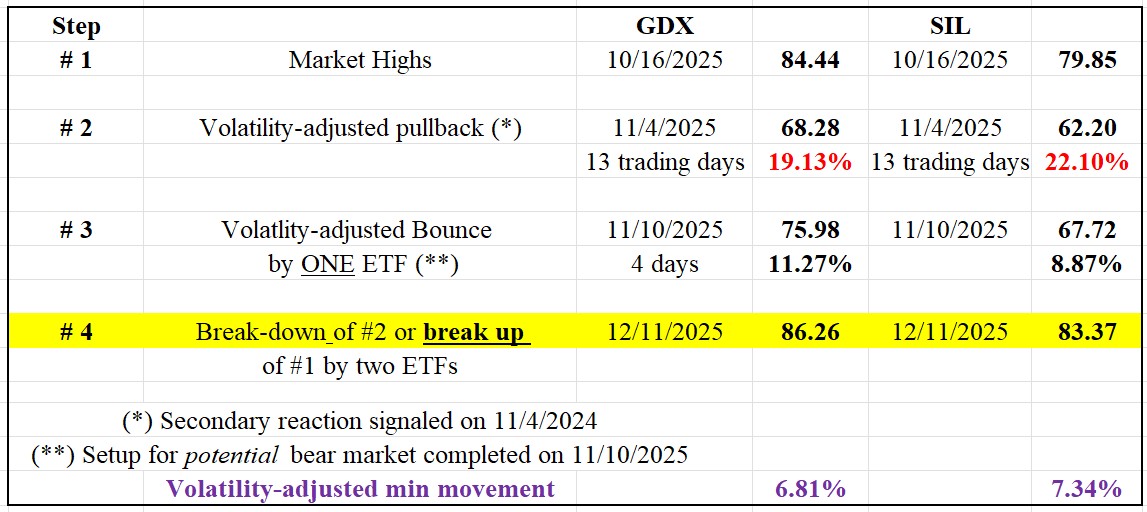

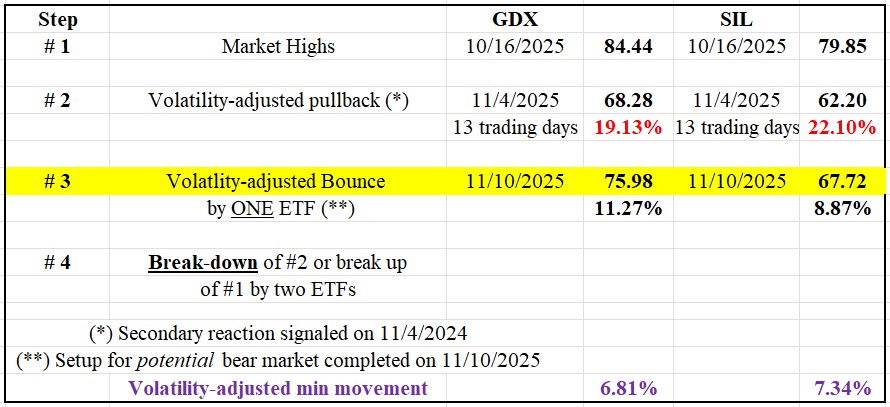

As of November 2025, Schannep Dow Theory (DT21C) signals indicate specific market positioning that informs Super Yacht Builders’ construction strategy for 2026-2027 should be expanded. The most recent signals indicate market volatility, with SELL signals generated in the summer of 2025, followed by a subsequent BUY signal in 2025. This suggests that markets have entered a confirmation phase for the current bull trend, although recent volatility indicates mature bull market conditions.

For shipbuilders, this signal pattern suggests a posture in the first year, characterized by “cautious optimization.” The bull market is confirmed, but maturity indicators suggest that approaching inflection points are on the horizon. The broader strategic context supports counter-cyclical positioning for 2026-2028. The global UHNW population is projected to reach 676,970 by 2030, representing continued secular growth. Asia, particularly India and China, is expected to see significant expansion among UHNW individuals. This demographic tailwind offers long-term support for industry growth, providing stability beyond cyclical fluctuations.

Technology and sustainability trends are lengthening superyacht construction timelines and increasing capital requirements, which amplifies the importance of accurate construction timing. Hybrid propulsion systems, alternative fuel compliance, and environmental certifications add complexity and cost. Builders who commit during up markets face elevated engineering and production costs; builders who commit during down markets benefit from supplier pricing reductions.

For the next 12-24 months, Super Yacht Builders should monitor Schannep signals. If market conditions trigger new SELL signals, implementing a contraction posture will preserve capital for the inevitable subsequent capitulation phase. If bull market confirmation persists, selective growth can continue, focusing on contracted business and client quality. Regardless, the discipline of signal-following provides far superior risk management compared to sentiment-based decision-making.

Conclusion: Building Discipline into Strategy

Super Yacht Builders operates within an industry where construction timelines create a fundamental lag between decision and outcome. This lag is not unique to superyachts; all multi-year capital-intensive sectors face similar challenges. Yet the superyacht market’s dependence on UHNW wealth dynamics, combined with the strong correlation between equity market performance and demand, creates an opportunity: builders who master counter-cyclical timing can systematically outperform competitors who follow market sentiment.

The historical evidence from 2007 to 2025 is decisive. Builders who committed to construction during market bottoms captured 20-40% return premiums compared to average-market constructions. Builders who over-committed during peaks faced margin compression and demand challenges. The difference was not luck; it was discipline.

Jack Schannep’s New Dow Theory (DT21C) offers an objective framework for transforming understanding into actionable insights. Rather than forecasting and guessing, builders follow specific signals that have proven reliable over 120+ years. SELL signals trigger contraction. CAPITULATION signals initiate cautious entry. BUY signals trigger aggressive expansion. This discipline removes emotion and anchors decisions to objective market conditions.

For Super Yacht Builders specifically, the strategic imperative is clear: institutionalize counter-cyclical construction discipline through explicit decision rules linked to Schannep signals. Build when others panic; conserve capital when others speculate. Embrace the 2-3 year construction lag not as an unavoidable risk but as a strategic advantage when construction timing aligns with market cycles. Capitalize on the UHNW population growth tailwind by leveraging geographic and capacity positioning to expand customer bases. Maintain capital discipline and supplier relationships through complete market cycles.

The superyacht industry’s history from 2007 to 2025 provides a clear roadmap: builders who mastered strategic timing through objective frameworks, maintained capital discipline, and acted counter-cyclically consistently outperformed competitors who followed market sentiment. Super Yacht Builders’ path to superior returns in the next market cycle follows this proven methodology.

In superyacht construction, as in all cyclical industries, fortune favors the bold, but only when boldness is disciplined by rigorous analysis, adequate capitalization, and strategic timing guided by proven methodologies, such as Schannep’s New Dow Theory.

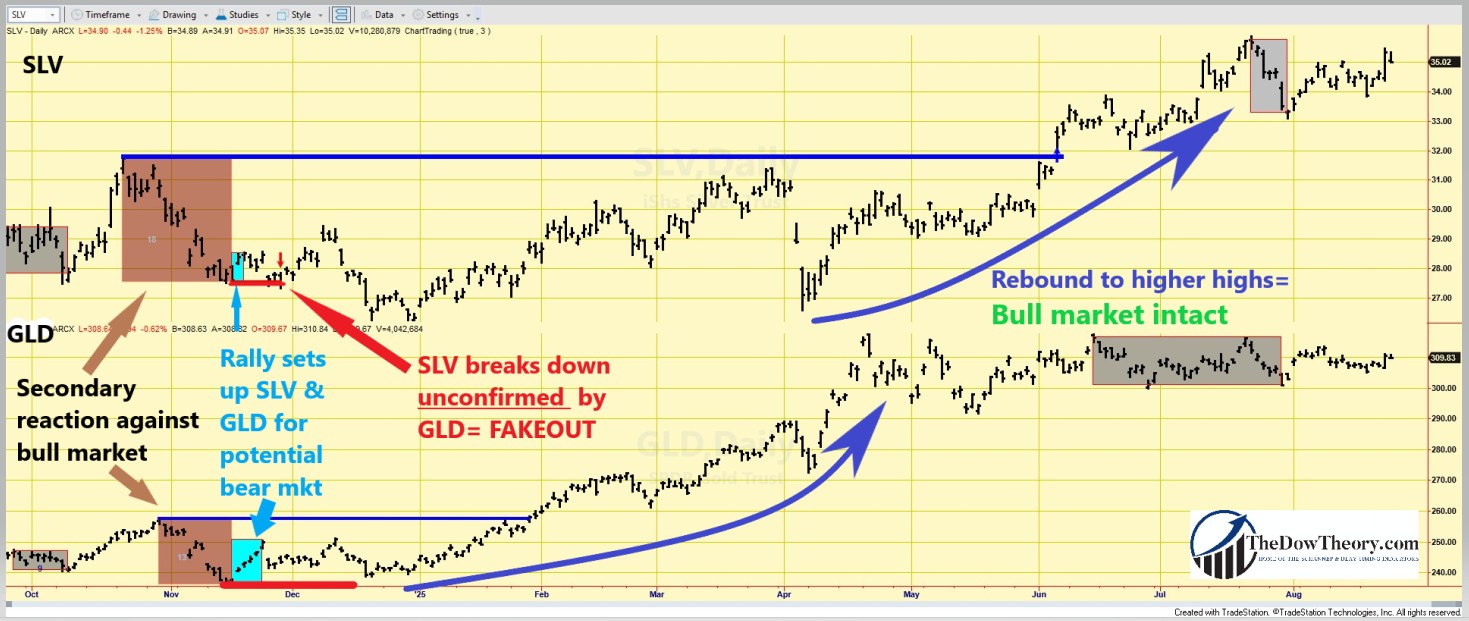

Second “fakeout” Breakdown: November 2024

Second “fakeout” Breakdown: November 2024